This post is part of a series, Reading Time at HSNY. Today’s article is guest-written by our intern, St John Karp, a graduate student in Library and Information Science at Pratt Institute.

Image 1: Swatch Skin “Silverize” (2000) displaying the time as @922 beats.

Alternative Ways of Telling the Time

In 1999 Swatch launched a satellite into orbit around the planet Earth. Sputnik 99 (or “Beatnik”) carried a radio transmitter designed to synchronize the time for Swatch’s “.beat” line of watches. These watches could tell the time using conventional hours, minutes, and seconds, but their selling point was that they could also display the time using Internet Time, a Swatch initiative backed by MIT that divided the day into 1,000 beats. The director of MIT’s Media Lab Nicholas Negroponte, channeling the argot of the dot-com era, said, “Cyberspace has no seasons and no night and day. Internet Time is absolute time for everybody. Internet Time is not geopolitical. It is global. In the future, for many people, real time will be Internet Time.”

The Horological Society of New York (HSNY) has an extensive collection of ephemera in its library, and during my internship, I was able to dig up a number of Swatch catalogs from the late 1990s and early 2000s that showcase Swatch’s attempt to reinvent time (see image 1).

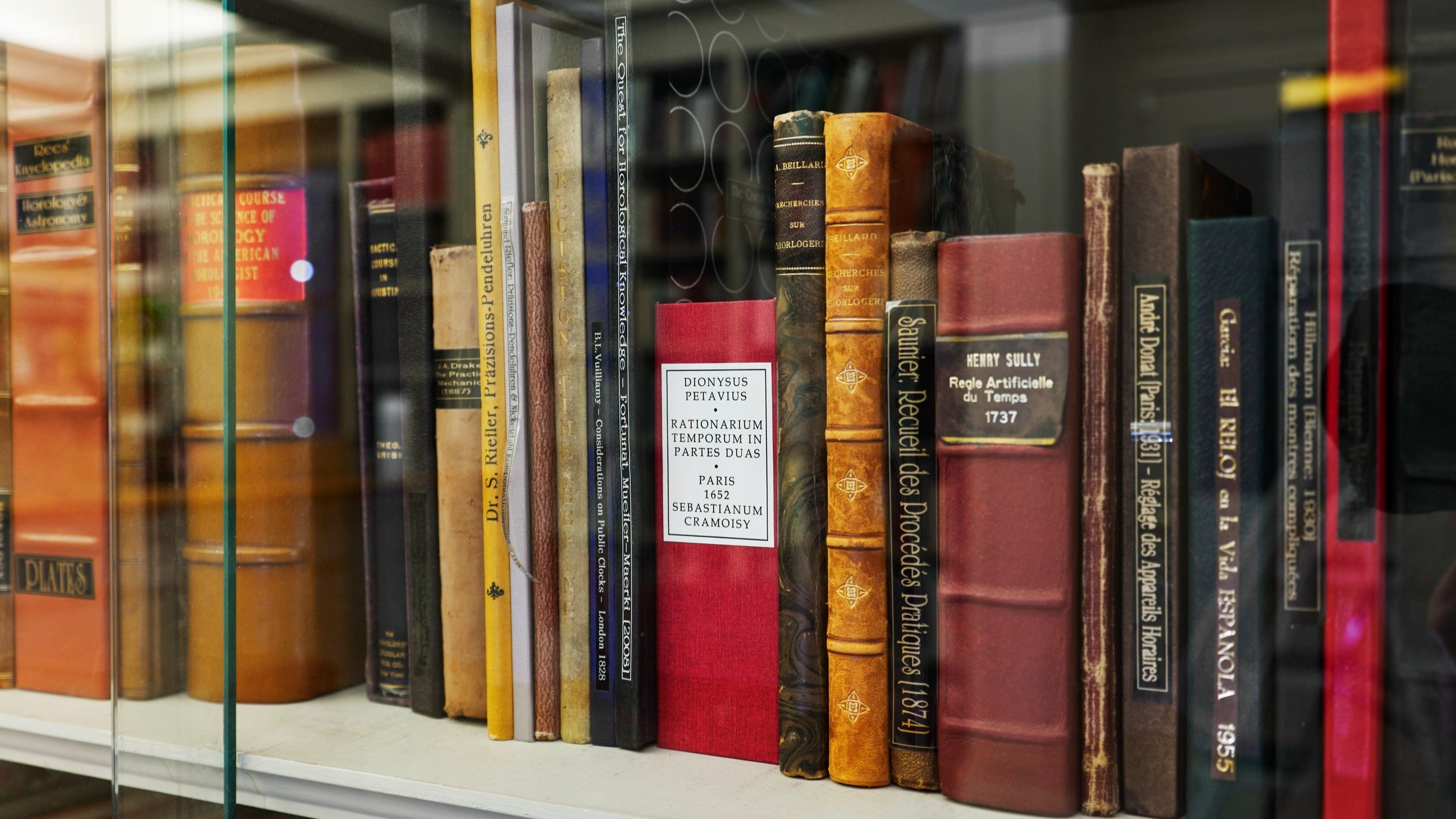

Decimal time and alternative time-keeping systems have a history as long and checkered as my pajama pants. The French revolutionaries in the 1790s proposed decimal units of time as part of the Republican calendar, which reinvented the calendar with new months and seasons and set the year One as the first year of the French Republic. Horologists such as Louis Berthoud made clocks and watches that displayed this metric time, and several of HSNY’s books detail the history of these gorgeous pieces (image 2). Sadly the Republican calendar did not outlast the revolution, though I’ve calculated that my birthday would have fallen on the first day of Thermidor — the month when people tended to get assassinated.

Image 2: A French Revolution-era clock with a ten-hour dial, from “La Révolution dans la Mesure du Temps,” a book in HSNY’s library.

In a similar vein, Fritz Lang depicted a 10-hour clock in his film Metropolis, both as an aspect of the film’s futurism but also as a symbol of the mechanization of humanity. In the same film, a man is made to function as a machine part by physically moving the hands on a large dial to match a sequence of light bulbs (image 3). Traditional Chinese timekeeping uses the shí, a unit of measure that divides the day into 12 hours (an interesting parallel to Western timekeeping). However, it also employs the kè, which represents one-hundredth of a day and places it squarely in the category of decimal time.

Image 3: A man clings to the hand of a ten-hour clock in “Metropolis” (1927).

The main reason a decimal clock failed to take off in Western timekeeping might be mathematical. When an hour has sixty minutes, a third of an hour is a round number that lines up with the twenty-minute mark. A decimal clock, on the other hand, with one hundred “minutes” in an hour, would mean that a third of an hour would be 33 ⅓ minutes and would not align with any indicators on the clock face. The twenty-four-hour day and sixty-minute hour are in fact so convenient that, in training simulations for the planet Mars, NASA employs a time system that simply stretches Earth hours and seconds to last slightly longer and sync up with the Martian day.

Perhaps another reason decimal time never caught the popular imagination is because it carries an element of the uncanny. George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four famously opens with, “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” The thought of a clock striking thirteen is so unnatural that it can presage the horrors of living under a totalitarian state. In Eugène Ionesco’s play The Bald Soprano the clock strikes as many as 29 times while two couples engage in alienating and unsettling dialog (see image 4). Like the distorted sense of space in Gothic literature, a clock that strikes the wrong number disorients us and fills us with a sense of dread.

Image 4: From “The Bald Soprano”: “[The clock] is contradictory and always indicates the opposite of what the hour really is.”

Don’t be fooled by the wreckage of the past, though. Decimal time is alive and well. Every Unix computer since the 1970s, which includes your MacBook and your Android phone, keeps track of the time in seconds elapsed since the beginning of the “epoch” (January 1, 1970). This number, currently somewhere in the one billion seven-hundred millions, is due for a reckoning in the year 2038 when it will grow so large it will overflow the computer’s ability to store it, similar to the crisis that happened in the late 1990s with the Y2K bug.

Of course if computer programmers are the only ones using alternative time systems today, they’re also the only ones joking about them. The furlong-firkin-fortnight (FFF) system of units uses the fortnight as the basis of its timekeeping. Paired with SI units this makes the microfortnight equal to approximately 1.2 seconds. The same sense of humor is probably responsible for the fact that Linux computers can still tell the date using the calendar of the Discordian religion (a stoner-inspired parody in a similar vein to the Flying Spaghetti Monster). My computer informs me that today is Sweetmorn, the thirteenth day of Discord in the Year of Our Lady Discordia 3190.

Image 5: Swatch Signs “Net” (1996)

Talk of computers brings me back to the dot-com era when the Internet was still shiny and new. Swatch had toyed with engaging in internet culture as early as 1996 when they released a watch that made prominent use of the @ sign (see image 5). Swatch, holding fast to the @ as an indicator of internet cred, repurposed it in 1998 as the beat symbol for their Internet Time. The premise of this timekeeping system was that it would be the same number of beats in any location around the world, neatly defenestrating the entire concept of time zones but failing to replace them with anything else. You could say to your friend in Norway or Australia, “Meet me in the chat room at @722 beats,” but you would have no idea whether 722 beats would be early in the morning or late at night. Swatch, perhaps guiltily aware of the flaw in their system, appeared to draw attention to it in a promotional video in which a man is woken up by a friend calling from a different country because the friend is using Internet time and doesn’t understand how early he’s calling. The two go back and forth about what time it really is, but the friend doesn’t get the concept of time zones now that he’s discovered Internet time.

Image 6: Swatch Skin “Shadiness” (2000) displaying the time as @431 beats.

The Planck time is the shortest unit of time possible given the laws of physics, but that is still longer than Swatch’s ill-starred satellite was operational. It ran afoul of commercial broadcasting regulations and had its batteries removed shortly before it was released into orbit from the Mir space station. It was decommissioned before they even pushed it through the airlock, and became garbage floating in space. Internet Time persisted as a key part of Swatch’s digital offerings for the next few years but the catalogs in HSNY’s library show that Internet Time had largely dropped off the radar by about 2003. The official Internet Time website, however, is still online and loyally informing me that it’s @583 beats right now. See you in the chat room!